|

Gilbert Murray MP's Westminster Blog Gypping in the Marsh in Times Past A Brief History of Gypping in the Marsh Gypping in the Marsh - the Murray Connection Dates in the Gypping in the Marsh Village Calendar Saint Bodkin and his Holy Well Abigail Morris: Britain's Last Anchoress Hemlock Hall Famous Gypping in the Marsh Artists Gypping in the Marsh Local Businesses |

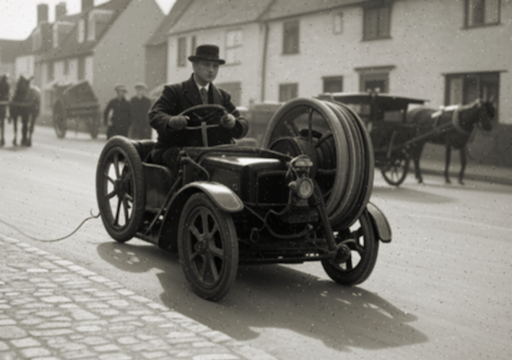

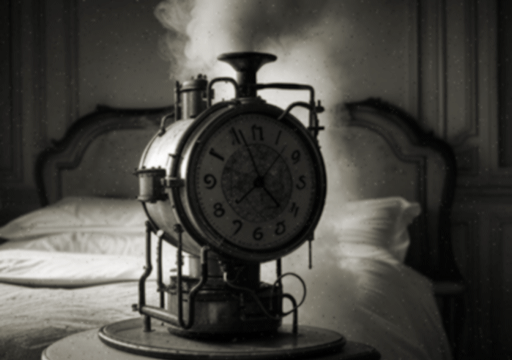

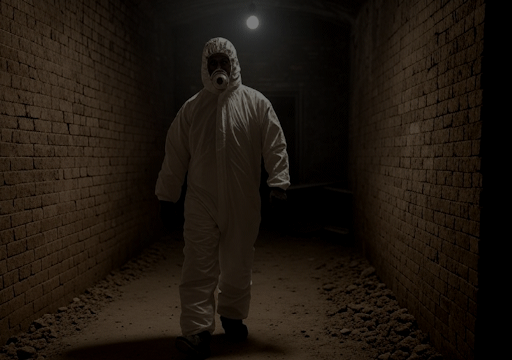

Hemlock HallHemlock Hall, the ancestral home of the Earls of Gypping, lies just to the north of Gypping in the Marsh and is one of the largest, grandest stately homes in Lincolnshire. The current Hall is a fine mixture of architectural styles, and in many ways the history of Hemlock Hall is the history of Gypping in the Marsh. Hemlock Hall is currently home to Lord Murray, the 18th Earl of Gypping, and his wife, Lady Elizabeth.  There follows a brief history of Hemlock Hall and the Earls of Gypping. The Origins of the Murray FamilyThe family of the Earls of Gypping is of Norman stock. The family (whose name was originally "de Meurray" until it was anglicised), came over to England with William the Conqueror during the Norman Conquest in 1066. The de Meurray family first came to prominence when a distant ancestor of the present Earl, Gaston Hirondelle de Meurray who was a knight in the King's service, assisted the Conqueror when he fell ill after eating a surfeit of lamprey. The grateful monarch granted Gaston the hereditary title of King's Keeper of the Privy, a title which has been proudly held by the first-born son of the family up to and including the present day. The somewhat onerous - and odorous - duties associated with the role were recently reduced to one purely ceremonial act per year, much to the relief of the present Earl.  The Granting of the Earldom of GyppingThe Murray family has been pre-eminent in English history from that day forward. The first Earl, Norman Stanley Fletcher Murray, was granted the Earldom of Gypping by Charles II the day after the King was restored to the throne. The first Earl had been one of the King's most faithful retainers all the way through Cromwell's Commonwealth, and risked his life on many occasions to perform his duties in the King's service. The Earldom of Gypping, and a substantial parcel of land in the county of Lincolnshire - centred upon the hamlet of Gypping in the Marsh - was his reward. The Construction of Hemlock HallThe first Earl lost no time in stamping his mark on his land by beginning the construction of Hemlock Hall on the edge of the village. It was not the best location to build a large manor house; as the name of the village suggests, the surrounding countryside is extremely swampy, and the original Hall sank into the mire just three years after it was completed. Nevertheless, the first Earl persevered, and found that the sunken timbers of the first Hall made an excellent foundation for the construction of the second Hemlock Hall, which forms the basis for the house that stands on the site today.  As the fortunes of the family grew in the intervening centuries, the Hall was extensively enlarged, but traces of the original Hemlock Hall are still visible in the cellars below the second ballroom. The 15th Earl of Gypping's Unique Taxidermy CollectionTaxidermy was extremely popular in the Victorian era, and the 15th Earl of Gypping was a keen practitioner of the craft. During his tenure, he filled room after room in Hemlock Hall with the results of his labours. While most Victorian taxidermists practised their art on animals, Lord Murray was unusual in that he stuffed the remains of his estate workers. Having started with Jenkins the Butler in 1848, stuffing deceased estate workers became a Hemlock Hall tradition - a tradition that endured right up until the 15th Earl's death in 1897. Despite the fact that some of the exhibits are now in less than perfect condition, showing signs of damage caused by mould, damp and rats, the 15th Earl's unique taxidermy collection is a highlight for visitors to modern-day Hemlock Hall.    The Coming of Electricity to Hemlock HallIn contrast to his taxidermist father, the 16th Earl of Gypping was fascinated by science and innovation and was always tinkering with one invention or another. In 1899 he brought electricity to Hemlock Hall, making it the first house in the village to have an electricity supply. While other electrical pioneers in English country houses relied on water management schemes or steam power to produce their electricity, Lord Murray preferred to use a more traditional power source for his dynamos. He installed two large wooden treadmills in the cellars of Hemlock Hall and entered into an agreement with Saint Bunty's Orphanage, under the terms of which the orphanage provided the manpower (or, to be more accurate, 'childpower') to power the dynamos 24 hours a day, in return for a small reduction in the orphanage's ground rent.  The orphan-powered treadmills proved to be such a cheap and reliable source of power for Hemlock Hall, with only the occasional maiming and fatality being recorded, that they remained in use until 1937, long after mains electricity had been introduced into the village. In that year, Lord Murray calculated that the cost of mains electricity had fallen below the cost of providing the treadmill-pounding orphans with gruel, crutches and coffins, so the treadmills were decommissioned and Hemlock Hall was finally connected to the mains.  The 16th Earl of Gypping and Lincolnshire's First Electric CarHaving brought electricity to Hemlock Hall, the 16th Earl of Gypping was keen to investigate whether it would be possible to use the hall's electricity supply to power a car. Many inventors were experimenting with electric cars in the early 1900s, but rather than installing batteries in his electric car as was the norm, Lord Murray chose to power his car using a fixed electric cable. One end of the cable was attached to an electric dynamo in the Hemlock Hall cellars, while the other end was attached to the car. As the car drove along, the cable paid out automatically, via a simple cable reel that was installed on the side of the car. Lord Murray initially discovered that the lights in Hemlock Hall dimmed significantly whenever he took his car out for a test drive. To get around this problem and to ensure that sufficient electricity was being produced to power both the hall and the car, he installed a third orphan-powered treadmill in the cellars of the Hall. Although the car worked well on the whole, the fixed electric cable was its 'Achilles heel': it frequently snagged on obstacles, and pedestrians and horses were prone to tripping over it. On top of this, Lord Murray never completely solved the problem of how to reel the cable back in once it had been fully unwound. As a result of these issues, after six months of experimentation, Lord Murray decommissioned the third treadmill, scrapped the electric car, and turned his attention to a more tried and tested technology: steam power.  The 16th Earl of Gypping: Steam Power PioneerHaving designed and built Lincolnshire's first electric car, the 16th Earl of Gypping funded the development of one of Britain's first steam-powered cars - the Murray Steamer - which went through several iterations before Lord Murray abandoned the idea. The following series of photographs show prototypes of the Murray Steamer at each stage of its development. Lord Murray had hoped that the Murray Steamer would be a runaway success and that sales of the machine would secure the future of Hemlock Hall, which was in need of expensive repairs to the roof and foundations at the time. However, the only things that ran away whenever Lord Murray drove his temperamental contraptions through the village on experimental runs were the village folk and their horses. The first photograph in the series shows the first Murray Steamer prototype making its way through Gypping in the Marsh in 1912. Lord Murray made several trial runs through the village in the summer of 1912 in this prototype, until a boiler explosion in August of that year resulted in the complete destruction of the vehicle, severe damage to two cottages on Spring Lane and the sad demise of two inhabitants of the cottages.  After the loss of the first prototype, Lord Murray went back to the drawing board and came up with the second version of the Murray Steamer, here seen in action in the streets of Gypping in the Marsh in 1913. At the end of the vehicle's second trial run, its boiler exploded in Hemlock Hall's stableyard, resulting in the complete destruction of the west end of the stable block and the unfortunate death of three stable boys.  The third photograph in the series shows the final prototype Murray Steamer on its first - and last - run through Gypping in the Marsh in 1914. In this final version of the vehicle, the driver and passengers are placed unusually high above the ground, in an attempt to get them as far away as possible from the temperamental boiler. The photograph captures the precise moment at which the Murray Steamer's boiler exploded. Miraculously, Lord Murray and his butler, who were at the helm at the time, escaped completely unharmed. The same cannot be said of the visiting group of choirboys from Cambridgeshire, who were walking along the road to Saint Bodkin's church at the time of the explosion and were caught in the blast. They lost five of their number. Shrapnel marks, left by the shards of red-hot metal that flew out from the exploding boiler, can still be seen in the stonework of the buildings that face the north side of the village green, as can several fragments of bones and teeth, embedded deep in the walls of the buildings.  After this final catastrophe, Lord Murray abandoned his attempts to develop a steam-powered road vehicle. He instead turned his attention to harnessing the power of steam on a smaller scale, and developed the world's first - and last - steam-powered alarm clock. The resulting explosion not only devastated the guest bedrooms in the south wing of Hemlock Hall in 1916, but altered the course of succession in the Biskitt family, who were visiting guests of Lord and Lady Murray at the time: the Viscount's eldest son was sadly killed in the blast. Lord Murray subsequently took up stamp-collecting as a hobby.  Declining FortunesUnfortunately, the 20th Century was not so kind to the Murray family. A combination of rising death duties, paying for repairs to the hall following the 16th Earl's steam power experiments and a number of ill-conceived business ventures (such as the 16th Earl's plans to ship coals to Newcastle and sell ice to the Esquimau) resulted in the family's fortune being dramatically reduced. Hemlock Hall TodayWhen the 17th Earl, died, the current Lord Murray inherited not only the Earldom and Hemlock Hall, but substantial debts. Ever since inheriting the title, the 18th Earl has striven to maintain Hemlock Hall and to prevent it from sinking into a state of total dereliction. To this end, the 18th Earl has enthusiastically pursued a number of promising business deals... most of them hailing from West Africa, for some reason.  Visiting Hemlock HallThe 18th Earl regularly opens Hemlock Hall to the public during the spring and summer months. Members of the public are requested not to walk on the grass and not to pick the cabbages. Following on from the success of the cellar tours that took place as part of 'Heritage Open Days 2024', Lord Murray is now offering tours of the Hemlock Hall cellars on the first Sunday of each month during the spring and summer opening season. As well as giving a fascinating glimpse of life 'below stairs' in Hemlock Hall, the cellars, which are normally out of bounds to the general public, contain elements of the previous versions of Hemlock Hall that used to stand on the site, making the tours particularly interesting for those with a passion for architectural history. Asbestos-proof protective clothing and masks are recommended for those interested in taking a cellar tour.  It is also possible to visit the newly-rediscovered Saint Bodkin's Well, which is situated in woodland within the grounds of Hemlock Hall. Lord Murray has graciously permitted access to the well to interested visitors, via a clearly-signposted permissive footpath which starts to the north of the churchyard. Opening Times and Admission PricesApril - September: Saturdays and Sundays, 2pm - 5pm. Admission prices: £4 per adult; £2.50 concessions. Cellar tours (the first Sunday of each month during the spring and summer season): an additional £10 per person; protective clothing and masks recommended. October - March: Closed to the public. Copyright 2003-2026 www.gilbertmurray.co.uk. All rights reserved. |